Chaaaaaang! “It’s been a hard day’s night. And I’ve been working like a dog”

This first chord that starts A Hard Day’s Night is one of the most recognizable and famous opening chords in rock and roll. It’s played by George Harrison on his 12 string Rickenbacker.

A hard Days Night

The other reason that it’s famous is because for 40 years nobody knew for sure what it was. Many guitar players have tried in vain to recreate the sound but have usually failed miserably.

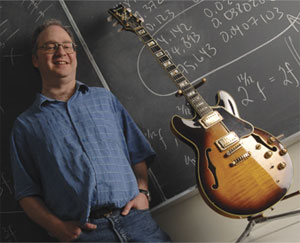

Well, someone has figured it out definitively – not a musician, but a Dalhousie mathematician.

Four years ago, Jason Brown was inspired by reading news coverage about the song’s 40th anniversary – so much so that he decided to try and see if he could apply a mathematical calculation known as Fourier transform to solve the Beatles riddle. The process allowed him to break the sound into distinct frequencies using computer software to find out exactly which notes were on the record.

What he found was interesting: the frequencies he found didn’t match the instruments on the song. George played a 12-string Rickenbacker, John Lennon played his 6 string, Paul had his bass – none of them quite fit what he found. He then realized what was missing – the 5th Beatle. George Martin was also on the record, playing a piano in the opening chord, which accounted for the problematic frequencies.

What he found was interesting: the frequencies he found didn’t match the instruments on the song. George played a 12-string Rickenbacker, John Lennon played his 6 string, Paul had his bass – none of them quite fit what he found. He then realized what was missing – the 5th Beatle. George Martin was also on the record, playing a piano in the opening chord, which accounted for the problematic frequencies.

The Beatles

I started playing guitar because I heard a Beatles record that was it for my piano lessons, says Brown. I had tried to play the first chord of the song many takes over the years. It sounds outlandish that someone could create a mystery around a chord from a time where artists used such simple recording techniques. It’s quite remarkable.

The Beatles producer added a piano chord that included an F note, impossible to play with the other notes on the guitar. The resulting chord was completely different than anything found in songbooks and scores for the song, which is one reason why Dr. Brown’s findings garnered international attention. He laughs that he may be the only mathematician ever to be published in Guitar Player magazine.

Music and math are not really that far apart, he says. They’ve found that children that listen to music do better at math, because math and music both use the brain in similar ways. The best music is analytical and pattern-filled and mathematics has a lot of aesthetics to it. They complement each other well. (comic courtesy of xkcd.com)

Music and math are not really that far apart, he says. They’ve found that children that listen to music do better at math, because math and music both use the brain in similar ways. The best music is analytical and pattern-filled and mathematics has a lot of aesthetics to it. They complement each other well. (comic courtesy of xkcd.com)

Hard Days Night Chord

So how was the chord played you ask? George Harrison was playing the following notes on his 12 string guitar: a2, a3, d3, d4, g3, g4, c4, and another c4; Paul McCartney played a d3 on his bass; producer George Martin was playing d3, f3, d5, g5, and e6 on the piano, while Lennon played a loud c5 on his six-string guitar.

Here is a Jason’s findings (PDF file).

Here is a really good discussion of the chord, what people thought it was, and what it really is. It’s a great article and a very interesting read.

Someone has also figured out the mystery behind Stevie Wonder’s Clavinet parts on Superstition. Check it out.

now if only someone can properly figure out some of sonic youth’s ghost chords on their early albums..

Saw the Bachman video. Great studio explanation. Here’s one of the better chords on a single guitar, 6 or 12 string, to approximate that sound, G11sus4 in this position (standard tuning):

e: 3

B: 3

G: 2

D: 3

A: 3

E: 3

That is not correct. Here’s an audio clip where Randy Bachmann (Guess Who, BTO, etc) explains being invited to Abbey Road studios by George Martin’s son Giles. Giles played it for him one track at a time, and he was able to pick out what each instrument was playing. He did, however leave out the piano part. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AvxPc5MPEuQ

Other than that – what was so special about it? It doesn’t sound particularly hypnotizing or amazing to me. And the fact that an instrument was missing in the attempts to reconstruct the sound doesn’t make it any more impressive. But maybe I’m missing the point? (I’m not a musician I must admit…)

Remember that the uniqueness of the sound of this chord is also related to the now vintage style Rickenbacker “Toaster Top” pickups and the 5th control knob most only found on Rickenbacker guitars. The fith control knob can be seen behind the larger front and back pickup volume and tone controlers.

Rickenbacker International Santa Ana. Calif.

What makes any one person think their interpretation is absolutely correct when there are soo many others who feel the same? Who’s to say Ringo didn’t lean up and squeeze out a little fart that was 20 cents between notes, sprinkling a little unquantifiable magic into the music? Or would some of you who think you have God’s ears say “Well, it’d have to be a fart in the key of F, there’s no other way.”

Maybe because this one person used fast fourier transform to separate the individual waveforms of the music and find out exactly what notes were played?

This isn’t an interpretation of the chord, it’s a mathematical analysis of the chord. There’s no debate in my mind whether the notes displayed by the FFT processing are right or not.

Any musicians out there with EARS?

Do this, please:

1) Take a good quality stereo version of the song and high quality headphones.

2) Pan all the way the right. Surprise. It’s mostly PIANO!

3) Listen closely. It’s basically a Gsus/D

Now, here’s something that apparently no one has heard: About half way thru the chord, C4 within the chord resolves quietly down to B4.

Sorry. All this effort, and no mention in the entire analysis of this B natural.

Nor does any transcription I’ve seen show this B.

Listen, you will hear it.

Yep. You’re right. Actually I hear a C resolving to B at least two octaves lower than that.

The researcher got the notes right but the distribution wrong. If you read George Harrison’s quote, it’s an “F” with a “G on top”. Fadd9. If you add the “D” that Paul et al played, the chord is an F6add9. Nothing more, nothing less.

Fourier transforms, by the way, can tell you the NOTES played, but not which instruments are responsible in an ensemble like this, especially instruments so harmonically related as guitars and pianos, thus they GUESSED at the instruments playing it. I agree with an earlier comment – John played only a high “loud” c5? I don’t think so. Just state the facts and don’t interpret them.

Wow, just think if we’d put this much effort and analysis into something REALLY important, we’d all be living on Mars right now driving flying cars and jetpacks (like ’60s sci-fi said anyway…) I want my Jetson’s car!!!

[…] Hard Day’s Night Chord-Dm7(9/11) February 13, 2010 reaktorplayer Leave a comment Go to comments via: NoiseAddicts […]

WHAT IS THE CHORD U NEVER MENTIONED WHAT IT IS I WANT 2 PLAY IT. I HAVE A BET ON THIS.

Too many pocket protectors involved here. George plays a simple 1st Position F with G added on 1st string/3rd fret.. just like he said in his interview about it. You can see his hand positioned for it at time index 0:25 in this Youtube video:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y2s4XJkx3qM

John plays a simple 1st position C5 at the same time, as seen at time index 0:20 of this video:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2ILEI-B18vo

On which fret Paul plays his D depends on the Bass. The studio version is his 4001 Flat-wound-steel-stringed-horseshoe-bridge pickup’ed-Treble-Plenty Rickenbacker. The live versions and movie scenes are played on his 500/1 Nylon-Stringed-Mud-Puddle-Poorly-Intonated Hofner.

Something unaccounted for in the nerd research project is that a Rickenbacker 12 is strung differently than any other 12 string guitar. So there are your problematic frequencies. Jeez.. The man was asked.. He told us. That’s what it is. Period.

[…] how to reproduce that chord either. Fast forward to 1998, when math professor Jason Brown finally unlocked the secret using Fourier transform analysis on the recording. What he found is that in addition to two guitars and bass, Beatles producer […]

The research seems to treat the recording as if it were sampling the actual instruments directly. The problem is there’s been no accounting for the Neumann U47 tube microphones, nor the EMI tube pre-amp desk they went through, nor the second pass through the tube mixer the recording was mastered with, all of which impart various order harmonics into the sound which will either cancel or reinforce sounds that may or may not be actually in the source material. I think it’s an interesting theoretical start, but flawed until the entire signal path is accounted for, including the format and playback device sampled from.

The question I’d like to know is “How did they come up with that chord?” Pretty amazing…whatever it is.

I don’t think it’s ever been a “mystery” that there’s a piano in there played by George Martin. Sounds pretty obvious to me.

And what about the snare drum hit? It’s a little surprising to see no mention of it in the analysis. Interesting discussion though.

It’s interesting but surely the point is here that it is a great song by a great band. The fact that the opening chord is causing debate forty-five years after the release only reinforces the genuis of the band.

this is a piece of cake. If you want a real challenge tell me what the last chord is of “Because” by the Dave Clark Five.

G6/9

I had no idea that this topic would show itself for discussion. So when I “Stumbled” over it, I had to comment.

“I remember the first time I heard these notes and recall the magic of that time. What is stranger is that, a new time is upon us. We can receive and understand more frequencies than we had previously realized. But the magic of “Beatles” will resonate forever in our universe along with us.”

What can you say about a researcher who says he was “surprised” that there was a piano in the chord? The piano is about 75 per cent of the sound of this chord, which is why the end chord of the song (it is a bookend, same chord) sounds different….there’s no piano at the end.

The volume is not gradually being raised as the chord rings out, there is a large amount of compression on the mix and you are hearing the compressor slowly release as the chord rings out.

George plays what he has said he plays. The piano is basically hitting a G sus with 2 “d” notes (in octaves) with the left hand. Those D notes are HUGE in the chord. The Ricky 12 is basically the highs you are hearing in the chord, the piano all the mids’ and lows. Paul doubles the D’s of the piano. It’s not the mystery everyone makes of it. You want mystery, start figuring out the polychords Nelson Riddle used in the string arrangements of Frank Sinatra recordings;)

TH

i do not agree with these findings, though one has to be impressed with the lengths that were gone to in order to reach them.

i have heard other recordings of this song from the same sessions that clearly illustrate what this is – 6 and 12 string guitars playing f major add 9 (with the open A string on the 12 string, at least, also present) and the bass guitar playing a D3.

i know this because i can hear it. perhaps that seems less certified than this study, but i’m telling you, that’s what it is.

This is the best thing ever! Thanks so much for sharing these findings. I’m going to show this to

1) my music appreciation students, who will now have it cemented in their brains that I am a lunatic;

2) my private students, to whom I always stress the connection between math and music (and physics); and

3) my brother, who’s a crazy musician/theory nerd/math enthusiast like me!

You should all get out more…

It’s an E11 Chord. Use your ears!

There are some really poor assumptions made in the research, which is why the answer that the analysis gives is flawed.

First, he arbitrarily selects one seconds’ worth from the middle of the chord, then imposes an arbitrary threshold on the fourier amplitudes. That’s why he didn’t see the F4 he expected to find from the 12-string guitar (it IS there, almost as strong as other nearby frequencies). This leads to incorrect conclusions about which notes are played by which instrument.

What he should have done was to take a few FFT slices of the chord, and look at how the amplitudes change over time. He should also have been more careful about losing valuable information by applying a threshold. This may provide much more reliable evidence to link groups of notes to specific instruments.

He also missed some of the lowest notes played on the piano (low D minor triad), and made some dodgy assumptions about tuning (he shouldn’t expect harmonics on stringed instruments to be integer multiples!).

Good idea to the do the work, but disappointing execution.

“if you listen to music and hear numbers, i feel very sorry for you.”

You don’t know very much about math, do you?

this is pretty cool, but all of you who think music IS math, you are completely missing the point. music is not math, any more than architecture is math, or painting.

if you listen to music and hear numbers, i feel very sorry for you.

The article linked above on everthing2.com has the following from George Harrison:

Q: Mr Harrison, what is the opening chord you used for “A Hard Day’s Night”?

A: It is F with a G on top (on the 12-string), but you’ll have to ask Paul about the bass note to get the proper story.

…which negates the “correct” math answer. GH should know, they played the song live about 100 times. Overtones and reverb can create lots of extra tones; I suspect this is where the math went wrong.

“Mathematics – language of the universe, core of everything…including music now”

Yeah, and for the last 2.5 thousand years if you know anything about Pythagoras, musical intervals and ratios.

I think its wonderful that your mathematical skills can dissect such an iconic sound of our generation! The instrumentation (including credit to our beloved 5th Beatle) is spelled out in BEATLESONGS by William J. Dowling. For any fan, this is the definitive book – and I am not a sales person or involved with it in any way. I bought it for my son, he never puts it down (cheap too!)

Great job – Thanks!

If you watch live clips you’ll see Paul playing a G on the bass on the third string & John an F9 chord in the first position. I haven’t seen any clips where you can see George’s chord.

I’d say I definitively played the right chord when I was 16 in 1967 when I was figuring everything out. Yes, the chord is elusive, but I think I had it “sussed”. It’s the G in the left hand of the piano that makes it sound like more of a polychord. Treated as a Dominant V chord, where D would be the bass note, it’s a D7Sus.4. With a G in the bass, the chord becomes a G6Sus.4.

The Sus.4 needs to be resolved whether you look at it as a I chord or a V chord. If Lennon is hitting a hard C,

(which I don’t believe to be the case.

I agree he’s not present, and it sound like Paul hits a D and they slowly raise the volume of his note), it just emphasizes the Suspension. And on the ending the D7Sus.4 is resolved to Minor7 on George’s riff. Great stuff!

hahahahahahahahahahahahaha wayne. oh my god, seriously.

Mathematics – language of the universe, core of everything…including music now.

OMG…it’s Charlie Epps from Numb3rs for guitar players! 🙂

A D11 chord played on a 12 string (Rickenbacker). I knew it when I was 15 (I’m 52 now).

Wayne – The link to the PDF at the bottom of the article answers your questions.

i’m sure i’m not alone in asking,what the hell is ” a2, a3, d3, d4, g3, g4, c4, and another c4 “….come on…i’ve been playing for 30 years and don’t know what this mans…more over i’m dead positive the freakin beatles don’t know what it means either…how bout some HELP !!!

It’s piano octaves, which correspond to specific frequencies. Middle C is C4, the 4th C up.

It’s a Dmin7 chord with a 9 and 11 tensions! It would be a way “weirder” chord is George Martin didn’t play that F. D9sus4

So no one has ever realised before that there was a piano in it? I can’t believe it. And then I seriously doubt Lennon played a single note. I really don’t think so.

It’s such a rich sound. Whenever I’m playing the CD in my car and the last song ends, it loops and the beginning always catches me off guard and scares me a little.

Very cool that the chord A Hard Day’s Night finally has been successfully

reproduced. Never expected mathematics

would be the tool used to solve it.

thanks from tony

Steinberger has a guitar which with the tremolo bar can shift all in tune the key of the chord up and down I just saw.

BYTE once had a BASIC “pseudo FT” program I used as my boss had taken soil resistivity readings down in Florida, perpendicular to the shore, but had moved the four electrodes in the ground in the wrong order consistently. So I was able to take the pattern of readings and turn them from hills and valleys into a trend which fit with the underlying geology, more moisture more conductivity or “susceptibility” of electrical current and no anomaly.

“Music and math are not really that far apart, ….

They are even closer than that! Music is the language of maths, everything in Music is based on numbers…

I think I could have told them it was a piano, but as for finding the notes to be played, I have no clue. There is a hint of that piano hammer “hit” and vibration that a guitar doesn’t make.

I’m not a trained musician, but have noticed that I can pick up fairly obvious things in music that trained musicians can’t. I have seen musicians say there is no similarity between songs because it’s in the wrong chord, or key or whatever. It’s either too high or too low, but my ear and several other untrained ears can pick up a similarity. It seems that a lot of musicians get hung up in notes, chords, etc. and lose the ability to see the forest for the trees.

They would probably say “Well that note can’t be made on a 12 string guitar… what is it?, they only had a certain number of instruments in there.” Give the song to a lay person and they can just say it “sounds like” a piano.

The FT generally has equally spaced bin-sizes. If you are interested in musical notes, then you just shift the poles on the unit circle to be logarithmically placed, they are linearly placed usually, and line one bin up with A=440 Hz, based on your sample rate. Then, you have bins centered on the standard notes… You can then subtract the known harmonics from the lowest notes in proportion to the instrument type and ID the rest… There is more to do, but you get the drift… Very easy from the definition of the FT and knowledge of what it really is…

sorry all except the first two f’s should be 4s and 5s.

And not only must Harrison be a liar, he also Harrison must have a really strangely tuned guitar to play what this mathematician apparently figured out with his computer.

Ummm George Harrison himself said he plays an Fadd9 on his 12-string

That’s f3, f4, a3, a4, c3, c4, g3, and g4.

Great! I was reading about famous chords in Wikipedia. There’s the “Hendrix†“Electraâ€, “So What†and other chords that are important. This one sounds too complicated to be in the same set!

Nice use of the FFT – and kudos for your functional OCD.

Totally wrong here. Randy Bachman gives us the actual guitar notes played after listening to the original multi track. Here it is. George plays an F chord with a G on top and a G on the low E string and a C on the 5th, on the 12 string. John plays a D sus 4 and Paul plays a D on the bass. Thats it. Heres the link wherein Randy explaines it all. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AvxPc5MPEuQ

I love that math & music are used together here,

but Alex above is totally right. And this video is

all the more credible since Randy got all his info

from Giles Martin, George’s son….

Problem is there were NO multitracks then. They only bounced 2trs in the early days. Sgt Peppers was first album using a 4tr machine. Revolver was done on 1″ 8tr. So Randy mention of ‘source tracks’ is misleading. Not sure what he meant unless they compiled it from mono tracks for 2tr machines…

They DID have mulitracks when they recorded Hard Days Night. It was a four track recording. I Want to Hold Your Hand was the first 4 track recording and that was late 1963. They did not go to 8 track until 1968 on the song While My Guitar Gently Weeps.